Why are Japanese knives the lengths that they are?

Categories

Sun and the moon

At the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic in February 2020, the people of Wuhan were the first among us to face the dark days of the spread of the disease and the answers of government. In response, individuals and community groups all over Japan dispatched ‘care parcels’ to the city, decorated with classical Chinese poetry offering solace and support to unmet friends.

We are distant, but we experience the same winds and live under the same moon.

It was ever thus. From early times Chinese culture and history have been woven into the Japanese story. Japan’s language, writing system, religious history and understanding, stories, measures and values have all been deeply influenced by its neighbor. Japanese today maintain a respect and even a reverence for the depth and beauty of Chinese culture, and understand how deeply that influence touches our daily lives.

That subtle influence is found in the dimensions of items we use every day. Our knives are one example.

At one time the Japanese archipelago had its own measures. With trade and increased contact with China, Chinese ways and means were broadly adopted and adapted and eventually became what we would understand to be ‘Japanese’. Until the mid-twentieth century the formal base unit of Japanese length was the shaku, based upon the Chinese chi.

As it was with standard measures, so it was with writing. It isn’t known if there was an existing Japanese writing system at the time China’s writing system was introduced to Japan, but in effect Chinese written characters became Japan’s. Things evolved, and in the Nara period that encompassed most of the 8th century, Japan’s dominant Chinese-influenced method of written communication was supplemented by two sets of uniquely Japanese characters, hiragana and katakana.

There’s a nice intersection between Japan’s writing system and the topic behind this musing, which is Japan’s traditional measures of length and how that relates to knife culture, and very likely the knives you own.

Hiragana is itself made up of simplified characters derived from kanji. The character ‘su’ (as in sushi) is written す. The kanji source is 寸, or sun. You can no doubt see and hear the influence.

‘Sun’ is the eastern equivalent of an inch, equal to 3.03 centimetres. Like an inch, one sun is said to be derived from the breadth of a thumb. Ten of them make up one shaku. There are twists and turns and offshoots to the story since its import into Japanese thinking, but that’s how things ended up for Japanese knives.

A quick note on pronunciation. The measure ‘sun’ is nothing like our sun in the sky. Instead it would be as if ‘soon’ rhymed with ‘book’. You can think of it as being the sun in ‘gesundheit’.

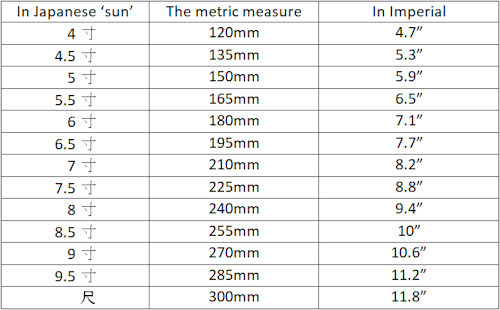

In modern terms, the approximate length conversions look like this:

Now you can see where we’re coming from. Your 240mm gyuto is 8-sun in Japan. Half-steps are common – your 225mm gyuto is 7.5 sun. That nice 150mm deba is 5-sun.

If you own a sashimi knife then you too can relate. Your 180mm yanagiba is 6-sun, and the 300mm masterpiece you caress or covet is one shaku.

There are no rules, just tradition and convention, and even those will vary from region to region. In Japanese knife making you will also see blade lengths of 140mm, 160mm, 200mm and so on.

But on the whole, in all our distant kitchens, together under the same ancient moon that inspired the Chinese poets of long ago, the length of our knives is guided by the light of sun.

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...